In Review

Tangled in birds and carousels: a look at in the circus of you

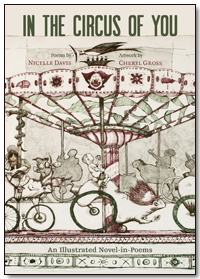

In the Circus of You by Nicelle Davis, illustrations by Cheryl Gross. Brookline, MA: Rose Metal Press. March 2015. 104 pages. $14.95 Paperback.

In The Circus of You is an illustrated novel-in-poems about the dissolution of a relationship and what to do with its remains. The book is a collaboration between the poet Nicelle Davis and the illustrator Cheryl Gross, who write in the endnotes that “the images and poems were created spontaneously and simultaneously through a yearlong email exchange—the art became a […] conversation between two women who were rummaging through the wreckage of their failed marriages.” What is salvaged here is the body, disjointed and fractured, so that it becomes a nightmarish, interior sideshow by way of Edward Gorey and Barnum & Bailey. If you chose this book for its aesthetic brevity, sorry. This is not breezy beach read. It is a book for a winter evening by dwindling candlelight.

Davis’s poems inhabit an off-center world, one where death is “a present of flesh—a chance to appease another’s hunger,” and where the wind is “singing for what’s buried—calling what’s lost up from compost.” When the novel pivots to a sequence of poems that reference actual sideshow performers, it feels at once natural and intimate in its view of loss. This sequence—the second section called “Recruiting Talent for the Appropriation Circus”—names the split-tailed mermaids, the conjoined twins, the lizardmen, and the giants that populated the circus sideshows of the past. They’re appropriated once more as metaphors for the body and the mind and the rings therein.

Circus attendees must enter the big top with an open-mind—willing to view something different from “prescribed humanity” as Davis and Gross call it. At the circus you set your expectations to watch a man put his head into lion’s mouth, or a woman tie her limbs into a knot and then unravel. Sitting in the audience outside the three rings, you might flinch less, because this is what you’ve paid for. Davis and Gross invert this idea—the circus is inescapable, because the circus is you. In her poem “Entering the Big Top of the Self Requires Help,” Davis writes, “The two birds arch their wings to make a place for my left—/ then right—foot. I begin the descent into the tent of myself.” What do you do when the circus is inside? When the clown is in your gut (“The Clown in My Gut”)? You crawl out.

The novel turns at the poem “The Mob of Freaks Protests”:

We, like you,

are wrongly

used. Close

your eyes and

let us all go.

Before this, the narrator watches as her life transforms into something freakish, something to be gawked at, but by the end she has pivoted, embraced herself, and her “body’s been redesigned for uncensored / feeling.” (“Reborn Inside-Out, My Life Is Explained To Me by My Six-Year-Old Son.”) It is a release, a reclamation.

Davis and Gross reference Tod Browning’s career-stalling 1932 film Freaks in the endnotes. The black-and-white film depicts sideshow performers—played by actual sideshow performers—who live their lives and fall in love and were portrayed not in a gawkish way but from a human and intimate vantage. Davis’s poems and Gross’s illustrations call back Browning’s approach: that these irregular shapes and patterns—human bodies in Browning’s case and a foundering marriage in the artists’ cases—are presented as empathetic. “The better I get at barking,” Davis writes, “the more difficult it is / to realize pitch from product.”

Gross’s art is a collection of grotesqueries and horrors: body parts fused to bicycle spokes, flesh contorted and tangled in birds and carousels. The novel’s third section—“The Clown Act”—has a series of illustrations so unnerving that it invites you to check and double check under the mattress, to shut tight the closet doors before bed.

The partnership—the synchronization of the poetry and illustrations—is an effective marriage. Taken by itself, the line “Incapable of flight, its wings reduce to / hands” is no stomach-churner, but Gross’s deft illustration of a bird with actual human phalanges instead of wings completes it. In The Circus of You is a taught 100 pages, it’s sticky, and its images remain, because when you inhabit an irregular world for a long enough time, it’s impossible to hold onto the memory of what was ever regular.

—Anthony Marvullo

what is fact and what is fancy: A LOOK AT the imagination of lewis carroll

The Imagination of Lewis Carroll by William Todd Seabrook. Brookline, MA: Rose Metal Press, 2014. 43 pages. $12.00 Chapbook.

Rose Metal Press publishes writing that falls between genres or melts them into something new. The Imagination of Lewis Carroll, the winner of Rose Metal Press’s Eighth Annual Short Short Chapbook Contest, offers a beautiful example of this genre bending. Author William Todd Seabrook paints brief anecdotes of Carroll's life. Seabrook uses the fantastical musing style of the famous author’s writing and, as a result, the biographical facts of Carroll the person become hard to separate from the fantasy world that Seabrook creates. It is true that Carroll had a stammer, for instance, but unlikely that his first and only sermon lasted for three days.

Each of Seabrook’s chapters winds up into itself perfectly. In "The Duel of Lewis Carroll" another man challenges Carroll to a duel. Carroll refuses as a pacifist, but—in the space of less than a page and with no blows thrown—Carroll "step[s] over Newry's broken body and walk[s] away." Newry, the challenger, is overcome by rage in the face of Carroll's wit. It's hard to even imagine this scene as a battle until the last sentence arrives and announces Carroll's triumph.

Each chapter appears as delightful and satisfying as this duel. By the end, it doesn't really matter what is fact and what is fancy. These anecdotes might be more true of Carroll's life than a biographers notes.

Seabrook handles Carroll’s life with care and dignity. He gives a nod to Carroll’s odd relationship with young girls, which historians have cast in varying degrees of perverse since his death. Seabrook neither ignores this dark underbelly nor assigns blame. As readers, we are left to decide whether Carroll’s stories and photographs are innocent or evidence. The Imagination of Lewis Carroll feels like a vacation into the fantastical, yet troubled mind of the father of the Jabberwocky.

As is suggested by a “short short” competition, this chapbook can be read easily in one sitting. William Todd Seabrook’s vignettes tickle the mind with wit and imagination. The stories are enthralling, easy to swallow, and left me hungry for the next page. Like all the best short reads, The Imagination of Lewis Carroll remains full of beauty when you return to read it again and again and again.

—Tovah Burstein

Anthony Marvullo lives in New Hampshire with his fiancee and cats. He writes restaurant reviews at medium.com/the-yelping.

Tovah Burstein lives in Chicago with her spouse, dog, and spider plant. She runs literacy mentoring programs for Chicago Public School students.